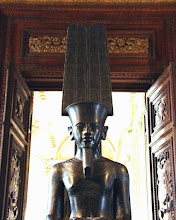

Egyptian Gems at the Freer

WHEN CHARLES LANG FREER was scouring the shops of Cairo's antiquities dealers a century ago, two falcon sculptures, pictured above, caught his eye. The "two great stone Hawks," he wrote at the time, "would nobly defend my little group of Egyptian art when permanently housed."

WHEN CHARLES LANG FREER was scouring the shops of Cairo's antiquities dealers a century ago, two falcon sculptures, pictured above, caught his eye. The "two great stone Hawks," he wrote at the time, "would nobly defend my little group of Egyptian art when permanently housed."

While amassing 1,400 items might seem a gigantic feat, Freer's Egyptian collection is fairly modest, with some of the best on display in a tiny room on the east side of the Smithsonian museum that bears the art collector's name. While most internationally regarded museums with Egyptian collections will show off a giant sarcophagus or two, or a golden funerary mask, the Freer has a fascinating showcase of small glass objects, including vessels, beads and amulets, which you could easily miss when strolling through its galleries. But if the Freer's Egyptian gems catch your eye, you could easily spend an hour surveying the array of diminutive but fascinating objects.

The collection should be a required stop at the Smithsonian museum, especially since there aren't too many Egyptian treasures in the museum collections in the nation's capital. It's also a nice retreat from the hustle and bustle of the Mall and the mind-numbing nature of the thousands of federal offices adjacent to the Smithsonian campus, perfect for a lunchtime or late afternoon visit, when you can have the place all to yourself.

The collection was assembled from 1906 to 1909 during three visits to Cairo and the various archaeological sites up and down the Nile Valley. While Egypt had always been a major stop for antiquities collectors, Freer — whose overall collection focuses on Asian art, along with an important holding of James Whistler's work — never put high priority on items from the Nile. But once he was there, he was hooked, writing to a colleague in 1907: "I now feel that these things are the greatest art in the world, greater than Greek, Chinese or Japanese."

One display case has a nice collection of small glazed vessels in rich blues and blue greens, dating to the 18th or 19th dynasties (1550-1196 B.C.) from the reigns of Amenhoteop II and Amenhotep IV, who is better known as the "heretic king" Akhenaten, the father of that legendary boy ruler, King Tut, Photo courtesy Freer Gallery of Artor Tutankhamun to Egyptologists. Back in their day, the vessels contained perfumes, ointments, scented oils and cosmetics.

A case full of amulets are also worth careful inspection and show that people throughout time have cherished small trinkets. The Freer's Egyptian amulets are made from ceramic, metal, glass or faience — a glazed composition molded by hand or pressed into a mold, much of it turquoise, a popular color. Many of the amulets, worn on necklaces or buried with the deceased to protect the soul during the afterlife, are from the 3rd Intermediate Period (1070-712 B.C.), including items depicting the god Bes and goddess Tawaret, which were amulets worn for safe childbirth and the protection of women and children.

Others include one of tiny papyrus-capped column holding up two cats and another of Duamutef, the jackal-headed son of Horus — worn to protect the stomach.

Unlike some exhibits, the Freer's modest Egyptian collection is easy to digest and shows that some of the best treasures in this city come in tiny packages.