Mystery mummy is lost female pharoah

Now that is what i call a find!

The mummy of an obese woman, who likely suffered from diabetes and liver cancer, has been identified as that of Queen Hatshepsut, Egypt's most powerful female pharoah, Egyptian archaeologists said Wednesday.

Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt in the 15th century B.C., was known for dressing like a man and wearing a false beard. But when her rule ended, all traces of her mysteriously disappeared, including her mummy.

Discovered in 1903 in the Valley of the Kings, the mummy was left on site until two months ago, when it was brought to the Cairo Museum for testing, Egypt's antiquities chief Zahi Hawass said.

DNA bone samples taken from the mummy's pelvic bone and femur are being compared with the mummy of Queen Hatshepsut's grandmother, Amos Nefreteri, said molecular geneticist Yehia Zakaria Gad, who was part of Hawass' team.

The mummy identified as Hatshepsut shows an obese woman, who died in her 50s, probably had diabetes and is also believed to have had liver cancer, Hawass said. Her left hand is positioned against her chest, in a traditional sign of royalty in ancient Egypt.

Molar in queen's jar fits in mummy's mouth

The discovery, announced Wednesday at the museum in Cairo, has not been independently reviewed by other experts.

While scientists are still matching those mitochondrial DNA sequences, Gad said preliminary results were "very encouraging."

Hawass also said that a molar found in a jar with some of the queen's embalmed organs perfectly matched the mummy.

"We are 100 percent certain" the mummy is that of Hatshepsut, Hawass told The Associated Press.

Hawass has led the search for Hatshepsut since a year ago, setting up a DNA lab in the basement of the Cairo Museum with an international team of scientists. The study was funded by the Discovery channel, which is to broadcast an exclusive documentary on it in July.

Molecular biologist Scott Woodward, director of the Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation in Salt Lake City, was cautious ahead of Wednesday's announcement.

"It's a very difficult process to obtain DNA from a mummy," said Woodward, who has done such research. "To make a claim as to a relationship, you need other individuals from which you have obtained DNA, to make a comparison between the DNA sequences."

Such DNA material would typically come from parents or grandparents. With female mummies, the most common type of DNA to look for is the mitochondrial DNA that reveals maternal lineage, Woodward said.

"What possible other mummies are out there, they would have to be related to Hatshepsut," he said. "It's a difficult process, but the recovery of DNA from 18th Dynasty mummies is certainly possible."

Molecular biologist Paul Evans of the Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, said the discovery could indeed be remarkable.

"Hatshepsut is an individual who has a unique place in Egypt's history. To have her identified is on the same magnitude as King Tut's discovery," Evans told the AP by phone from Utah.

Hatshepsut is believed to have stolen the throne from her young stepson, Thutmose III. Her rule of about 21 years was the longest among ancient Egyptian queens, ending in 1453 B.C.

Hatshepsut's funerary temple is located in ancient Thebes, on the west bank of the Nile in today's Luxor, a multi-collonaded sandstone temple built to serve as tribute to her power. Surrounding it are the Valley of Kings and the Valley of the Queens, the burial places of Egypt's pharaohs and their wives.

But after Hatshepsut's death, her name was obliterated from the records in what is believed to have been her stepson's revenge.

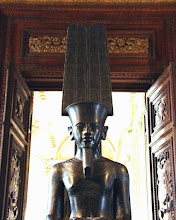

She was one of the most prolific builder pharaohs of ancient Egypt, commissioning hundreds of projects throughout both Upper and Lower Egypt. Almost every major museum in the world today has a collection of Hatshepsut statuary.

British archaeologist Howard Carter worked on excavating Hatshepsut's tomb before discovering the tomb of the boy-king, Tutankhamun, whose treasure of gold has become a symbol of ancient Egypt's splendor.