A royal destruction

Jill Kamel on a project that sounds the alarm for the survival of Egypt's ancient Valley of the Kings

Jill Kamel on a project that sounds the alarm for the survival of Egypt's ancient Valley of the Kings

Throngs of tourists crowd daily into the priceless tombs in the Valley of the Kings, brushing against walls and, even, tracing reliefs with sweaty fingers photos Matjaz Kacicnik

When first unearthed early in the 19th century, the royal tombs on the Theban necropolis, although stripped of their spectacular funerary contents, were nevertheless found in a remarkable state of preservation. The splendid painted reliefs retained colours as bright as on the day they were painted. However, plunder, desecration, exploration, environmental pollution and tourism have since taken their toll, and although successive efforts have been made to protect the tombs in the Valley of the Kings the prospects are grim. The marvellous decorations are decaying more rapidly than they can be restored.

Monks and hermits who hid in the royal tombs early in the Christian era were responsible for some of the damage to the decorated walls. Evidence of their habitation can be seen in graffiti -- which today form part of the historical record -- and blackening, probably caused by efforts to light up the tomb. It was after their discovery by 19th-century European explorers, however, that the tombs suffered most lamentably -- usually from their taking 'squeezes' (mouldings on wax or wet paper) directly from the delicately painted walls, but even from total loss when they forcibly hacked out masterpieces for exhibition abroad, sometimes destroying a substantial part of the surrounding plaster layer on the walls.

Among those who first recorded the scenes and inscriptions were Ippolito Rosellini, a colleague of François Champollion, who deciphered hieroglyphics in 1822, and Emile Prisse d'Avennes, the able craftsman who arrived in Egypt under the patronage of Mohamed Ali in 1827. D'Avennes made splendid detailed copies of wall decorations, some of which had already disappeared by the time he returned to Egypt, in 1859.

Tourists today pose no less of a threat. With large groups pressing into narrow corridors, the increase in humidity is a major problem. Darkened areas near some of the most striking scenes, particularly at the corners of gateways or on pillars, are probably due to the walls being touched, and there is even evidence of scratching.

Dina Bakhoum, a young Egyptian engineer specialising in restoration and conservation of monuments, brushes aside the suggestion that there is no way to stem the tide of destruction of the tombs so long as tourism remains a mainstay of the Egyptian economy. She concedes, nevertheless, that serious action must be taken immediately to ensure that this valuable artistic and historic heritage is protected for future generations.

Bakhoum is working under the direction of Kent Weeks, director of the University of Chicago's Theban Mapping Project (TMP) in collaboration with the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA). The aim of the project is to carry out a photographic survey, identify problems, specify the cause of the deterioration, and describe the technical questions related to the type of damage observed.

"Most of the tombs are structurally stable," says Bakhoum. "Some of the cracks and fissures in the bedrock are due to the nature of the rock. When cracks run from one wall to the other across a corridor over a ceiling, they represent no real danger to the tomb, even though they cause loss to a narrow section of the plaster layer. The most serious damage is the actual detachment of the decorated plaster from the background surface and unfortunately no modern technology can identity where there is such a threat. The best method is to gently knock the plaster to identify hollow areas.

"That may sound simplistic," she adds, "but the naked eye is an extremely effective tool. Only through the power of observation can one identify mere powdering of the plaster layer, from total disintegration, or damage caused by natural shrinkage. Such testing successfully reveals potential danger zones where action needs to be taken."

Flaking and loss of paint in the upper reaches of the walls of some tombs or in the corners of the ceilings may result from the concentration of high humidity in those areas, Bakhoum adds. "Loss of the paint and the plaster layer in other areas may have been caused by wasp nests, while blackening on the upper surface of the tomb walls near the ceiling appears to have been caused by bats," she says. In numerous tombs rounded wooden inserts were noted at almost equal intervals in the upper walls. "We have identified these as inserts for electrical cables. Tomb number KV 6 in fact still carries the old cables," Bakhoum says.

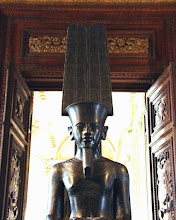

The Royal Valley is less than two kilometres from the edge of the Nile. Today, a tarmac road from the edge of the river makes the distance seem short. Before its construction, however, a visitor had a sense of the arid remoteness of the site chosen by the Pharaohs of the 18th, 19th and 20th dynasties (1567--1080BC) for their tombs. Eighty-odd tombs are currently known. They are relatively simple, comprising a series of rock-hewn chambers joined by corridors, differing only in length and in the number of chambers which represent stages in the journey of the deceased pharaoh through the underworld. Absorbed by the ram-headed Sun-god in his solar boat, and surrounded by a retinue of deities, the Pharaoh is depicted passing from one leg of the journey to another through massive gates guarded by serpents, protected by gods and goddesses until he reaches the judgment seat of Osiris, lord of the underworld, where he is judged worthy of a life everlasting. No two tombs are precisely alike, as priests developed differing explanations about the nature of the sun's journey through the night sky, and the king's journey to the netherworld.

"There are also different types of tomb adornment in the Valley of the Kings," Bakhoum says. "The choice of technique relates to the dynasty in which each was constructed, or in some cases depends on the nature of the rock. Where the rock was sound, the decorations could be carved directly onto the wall, but in other cases it had to be plastered first. Each method is now being studied. The type of damage or deterioration is being observed, their causes analysed, and restoration techniques are being considered. Some tombs have suffered a total loss of the plaster layers, revealing the bedrock beneath. In others there is only the loss of the thin plaster layer. There are also such problems as dust accumulation, salts efflorescence, and incrustations on the blue and green pigments."

Bakhoum speaks in a way that denotes intimate knowledge of, and concern for, the tombs she is studying. "We do not yet know the cause of some very strange black incrustation that appear on the blue and green pigments, but which do not appear on any of the other colours," she says. "We need to understand this phenomenon and to determine whether it is a chemical reaction to this particular type of pigment or dust accumulation that reacts in a different way on these particular colours. It may of course be a reaction to the use of certain consolidants."

In the last 30 years, the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation -- now the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) -- has taken numerous steps to safeguard the tombs. They have built a new terminal for tourist buses; they have removed the rest- house facilities in the central valley, which drained into the porous limestone bedrock, to what is considered to be a safe distance from the tombs; and they have laid down ground rules including the batching of visitors according to the size of the tomb. Unfortunately, these rules are not strictly adhered to. Tourism and conservation make bad bedfellows, and, as the pace of the former increases, the odds favour destruction over protection.

The construction of an international airport at Luxor has proved to be a disaster insofar as protecting Egypt's ancient heritage is concerned. The number of visitors to the Valley of the Kings has increased to more than 7,000 per day in the peak season. Dust is raised as groups huddle into corridors and tiny chambers; reliefs are spoiled as visitors brush against walls; and quantities of harmful water vapour is introduced into the confined spaces. The SCA is making every effort to control the situation by stipulating that only 14 tombs in the royal valley are to be open to the public, and no more than 11 at any one time, on a rotating basis. The others are closed either for their protection or to enable restoration.

The SCA has installed glass panels in some of the tombs in order to protect the reliefs, but, as Bakhoum explains, despite their advantage, glass panels do have serious disadvantages that might result in the actual deterioration of the painted reliefs. "The tomb is not a sealed environment like in the museum, so while the glass protects the walls from human contact, because of the narrow space between the glass panel and the wall there is a risk, while cleaning the glass, of touching and damaging the decorations. Nor does the glass reach the tombs' ceilings; while that itself is not a disadvantage as it is decorated, it does not prevent dust from settling on the walls."

The TMP is suggesting to the SCA that the existing glass panels be removed and replaced by panels only about one metre high, placed at a safe distance from the walls at the height of the average person's hands. "This would prevent people from touching the decorations and at the same time enable easy cleaning of the glass," Bakhoum says. "Unfortunately, the present glass panels are almost two metres high and are very heavy and difficult to remove."

So what chance do the tombs have, especially when they also have to contend with nature? Every decade or more, Luxor is subjected to particularly heavy storms and flash floods. The physical effect of torrents of water flowing down natural valleys carrying lumps of rock and earth further compounds the problem. Efforts have been made to control the storm effects by constructing protective walls around the entrances to the most vulnerable tombs at the lower point of the stratum, but how effective this will be in the face of a future major flood remains to be seen.

More than a century ago, the importance of carrying out an epigraphical record of all standing monuments in Luxor was recognised, but surprisingly only now are full descriptions and photographs being made. "Each wall in every corridor and chamber of each tomb, from the floor to the ceiling, and on every column," Bakhoum says of the inventory now underway. A general plan has been drawn up to show the location of the walls so documented. "We are creating a valuable database from which to work," Bakhoum says. "Never before has such a survey been carried out visually, which is really surprising because the actual condition of each tomb is the first step towards establishing the cause of damage and evaluating the best method to curb further destruction."

Is this a losing battle? A perennial problem is dust accumulation on almost all the tomb walls, causing the colours to appear darker and dimmer than they really are. Apart from that, there is no regular maintenance or cleaning and so the dust, along with the high humidity in the tombs, makes it stick to the walls. This is very damaging because, as Bakhoum explains, it becomes heavy and causes the underlying painting to detach from the wall.

There are, nevertheless, many advantages to documentation through photography and condition surveys, and Bakhoum is optimistic: "Photographs taken over successive years will form an accurate database and provide a detailed record of the condition of each tomb. The images already collected provide historical depth to the records, and by re-photographing on a periodical basis (say, every 10 years) changes in the condition of each tomb will be monitored."

Considerable progress has already been made in the last two years. Work continues. And on the basis of the results of the study, recommendations will be made for the future protection of the tomb decorations -- whatever is left of them, that is.

Source